☁️ Hi everyone, Robert here! I hope you’ve been enjoying Airframe on Tuesdays and The Deep End on Thursdays. If you haven’t subscribed yet, join the hundreds of aerospace executives, investors, and enthusiasts who read this newsletter.

Vertiport is one of the official buzzwords of 2023. The Economist editorial team dubbed them “half-airport, half-subway station,” and astutely speculated that vertiports “will be needed if eVTOLs are to get off the ground.”

They’re right, but I suspect they don’t realize how right they are. If eVTOLs are going to become a viable mode of transportation; if drone shipping is to become prevalent; in short, if air mobility is to transform the way we move, we don’t just need vertiports—we need gobs of them.

Vertiports in the wild

Technically, vertiport isn’t a new word. There are at least two “vertiports” currently operating in the U.S.

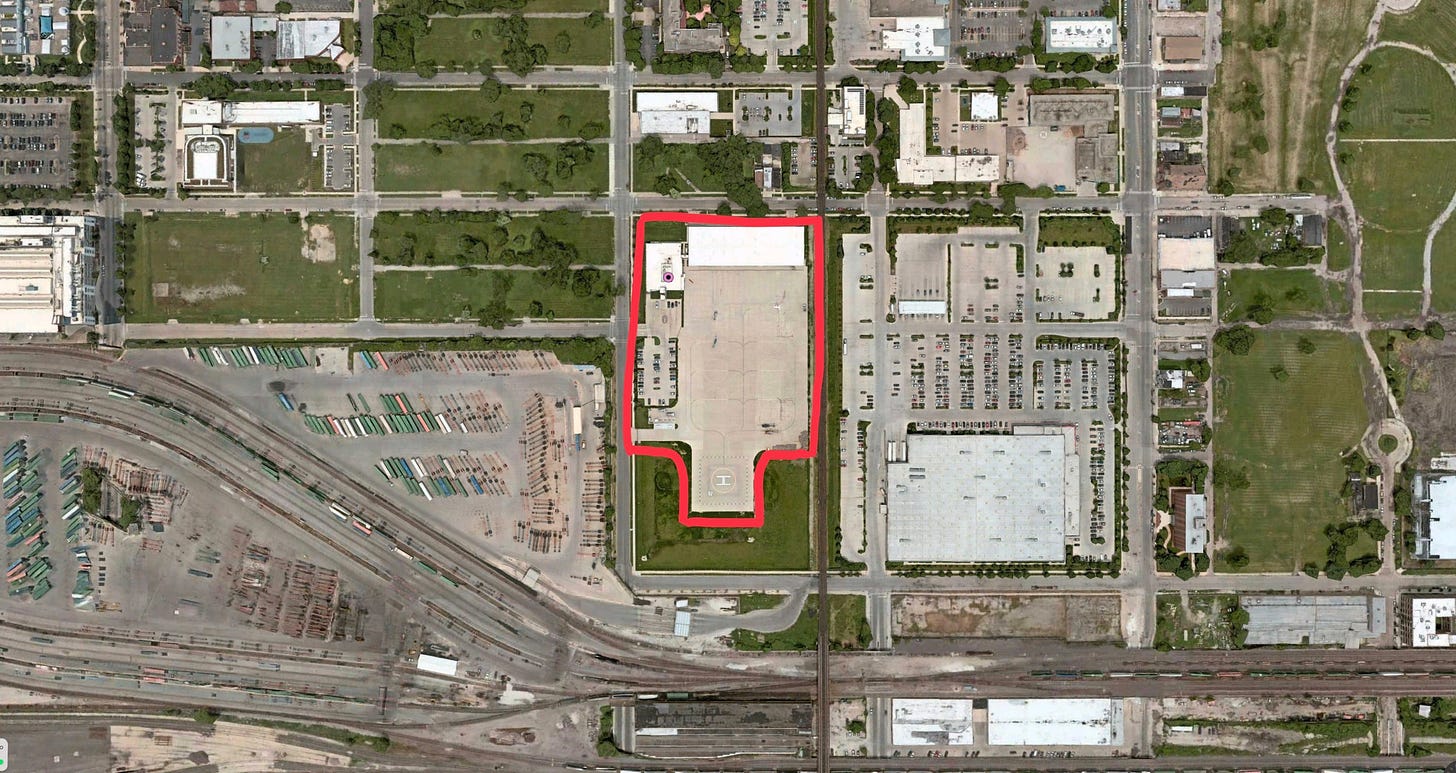

The Dallas Vertiport has been in service since the 1990s. With over 150,000 square feet of flight deck, the landing site was initially constructed for air taxi operations using helicopters and tilt-rotor aircraft such as the V-22 Osprey. But air taxi services are expensive for most people, and today the site receives only sporadic visits—most of them touch-and-go landings from media or law enforcement.

Opened in 2015, the Vertiport Chicago is North America’s largest and Chicago’s only helicopter landing facility. It hosts charter flight services, sightseeing tours, and emergency-medical flights. It appears to be busier than the Dallas Vertiport and has plans to welcome future eVTOL landings, but it doesn’t currently appear to be a significant air taxi service hub.

Why vertiports? Why not just call them heliports? The distinction is subtle but critical: vertiports aim for high-volume throughput and may include scheduled operations. They integrate with existing transit systems rather than serve as one-off landing sites.

Despite using vertiport in their name, neither Dallas nor Chicago has reached its potential as one. Traffic at these locations is far from high-volume, and there’s little proof that they are integrated with a broader mobility network. They have some of the right ingredients, but not the whole recipe.

With the help of advanced air mobility (AAM), their fate may change. EVTOL fares will be significantly less expensive than fares for traditional rotorcraft, and as prices go down, demand for air taxi services will go up. Pending community acceptance (which is ultimately about noise), Dallas and Chicago could soon be real vertiports.

Trunk and branch routes

Late last year, eVTOL developer Archer announced its first route in partnership with United Airlines, connecting Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) to Downtown Manhattan Heliport.

EWR to Manhattan is a popular route—over 30 million cars pass through the Lincoln and Holland tunnels each year. Surely this will be a good business for Archer, right?

Here’s some rough math: if the distance between EWR and Manhattan is about 10 miles, and Archer charges $3-4 per passenger-mile, carrying 4 passengers on approximately 100 trips per day, that’s somewhere around $5M in annual revenue. Archer and United will likely share that revenue; for the sake of simplicity, let’s say Archer earns $2.5M.

$2.5M is a decent business, but not for a company valued at over $600M (Joby’s market cap is even higher). Archer of course won’t stop at their first route; they’ll expand to include other “trunk” routes in NYC and other major cities. Then they’ll move to “branch” routes that connect passengers to surrounding communities. Within a number of years, they’ll be able to justify their current valuation.

But Archer, Joby, and the other eVTOL developers want to grow; they see their potential as something akin to Uber or Lyft, tech companies that do billions in annual revenue. To achieve that kind of scale, eVTOL startups will need thousands of routes just like the one mentioned above—and that means thousands of vertiports.

Location, Location, Location

You don’t meet ambitious business objectives without delivering what customers want. Most of them won’t be dying to ride in an eVTOL; they’ll want to get somewhere specific. The promise of AAM is that it saves people time so they can spend it how they want to. In that context, location is everything.

In a study on ground infrastructure for urban air mobility (UAM), McKinsey & Company ties the success of the industry to the location of infrastructure:

The location of the infrastructure will determine market-conversion levels. The closer a passenger is to a takeoff or landing spot, the greater the potential for time savings. If a landing spot is too far away from the origin or destination, the customer might not save enough time for a UAM trip to make sense.

Think of vertiports as nodes in a network. When Ray Tomlinson sent the first email in 1971, he sent a message between two computers that sat right next to each other. Hardly useful. But as the network grew with more and more nodes, email became a vast, powerful tool, and is now the means of reading The Airframe every week (email has other noble purposes too).

Similarly, the AAM ecosystem is only valuable insomuch that passengers have maximum optionality when it comes to ground infrastructure.

Old and new

We know what’s needed: thousands of vertiports in desirable locations. Building a huge network of landing sites will increase the value prop to passengers and allow eVTOL companies to achieve scale.

There are two ways to do it: construct new infrastructure or leverage existing infrastructure.

Several companies are working on new infrastructure: new entrants like Volatus and Skyports have released beautiful renderings or launched functional vertiport prototypes. Industry veterans like Ferrovial and Groupe ADP are in the game too.

These vertiport developers are focused on creating the optimal passenger experience, providing charging and other infrastructure to eVTOLs, and driving industry standardization. Purpose-built vertiports will be crucial for the early routes in the AAM ecosystem and will accelerate industry growth.

In addition to building new vertiports, we should be leveraging the ground infrastructure that is already available today. Thanks to an aggressive build-out of regional airports during the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. is flush with infrastructure suitable for small aircraft landings.

Surf Air Mobility, a fixed-wing player in the broader air mobility ecosystem, recognized the value of regional airports in their S-1 slide deck.

Regional airports are also great because they tend to be underutilized. In that sense, they’re nearly perfect for AAM. They’re just missing one key component: charging infrastructure. Fortunately, I’ve heard many airport managers say that they are already making plans to build charging capability.

Choosing to focus on either new infrastructure or existing infrastructure would be a false dichotomy. We need both.

What’s in a name?

The definition of vertiport is undergoing important changes: in Dallas or Chicago, a vertiport has been a place aiming to provide air taxi services as part of an integrated transit system. With eVTOLs, those sites may finally be able to reach their potential as vertiports.

As we get closer to the maturity of the AAM industry, the word vertiport is beginning to mean something more: it’s becoming inextricably linked to the advent of electric vertical take-off and landing aircraft. Charging infrastructure will be key. In some ways, vertiports are a symbol of our future of unbounded human mobility.

Billions of investor dollars have poured into eVTOL startups, and if these companies are to reach scale, they’ll need a network of thousands of vertiports. It all comes down to delivering what passengers want: convenience, optionality, and affordability.

I applaud the work that’s been done on new vertiports, but we must also make use of the stuff we already have. Only then will AAM get off the ground.

www.skyportz.com has Australia covered